Today we celebrate that we reached a point of no return with the Bogotá Metro

Why the city needs a metro

Bogotans are currently battling some of the worst traffic in South America. Last year, traffic data agency INRIX ranked the city as being among the 15 worst capitals for traffic in the world. Furthermore, global traffic database Numbeo estimates that in one year, 766kg of CO2 is produced per passenger. This would require about nine trees planted per passenger to produce enough oxygen to offset the CO2.

In its report, CONPES admits that public transport ridership is on the decline, while use of private vehicles is on the up. On a typical day, around 60,000 individual car trips are taken. The Bogotá Metro is intended to counteract this trend.

Costing an approximate $4.1bn, the project will be financed with $3bn from national government funds, as well as $1.28bn from the city municipality. This funding approval brings the network closer to delivery than it has been at any stage in its previous 70 years of talks.

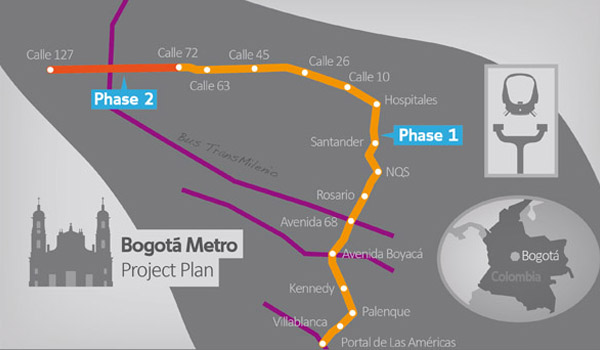

Once completed, the network will cover 24km from south-east to north-east, pretty much following Avenida Caracas, a major transport artery for the capital which will be given an urban revaluation at the same time.

About 20 trains, made up of around six cars each will provide enough capacity to carry 72,000 passengers each hour through 15 stations. It will reach a speed of 40km per hour. In a press release issued on 25 September 2017, Peñalosa thanked Colombia’s President Juan Manuel Santos and the national government for approving the funding, saying: “Today we celebrate that we reached a point of no return with the Bogotá Metro.”

According to Systra, the transport planning consultancy selected for the project, the chosen viaduct will allow for a quicker building schedule, while the network’s design will have to also take into account the highly seismic context of the capital. Colombia’s most seismic place, Mesa de los Santos, which experiences some 40 tremors each day, is less than 400km away from Bogotá.

What’s more, the network will also have five feeder lines that will allow ‘thousands of people’ from the boroughs of Soacha, Bosa and Kennedy to access the metro. Calculating the overall reduction in commuting times, pollution and accidents caused by private cars, supporters estimate that for each peso invested, 1.21 pesos will be returned.

“It is the first time that a metro project, of the seven that have been designed in the past in Bogotá, reaches this point of maturity and passes to this instance,” said Andrés Escobar, manager of the Metro Company, adding that this “is a reason to be satisfied and happy”.

Credit: SYSTRA

An elevated line would be 28% cheaper to operate, while the construction time would be reduced

An ELEVATED RAILway line

Over its lengthy planning process, the project has shapeshifted to become both a handy political tool to mention ahead of key elections and, mainly to citizens, a hopeless pursuit. But for the majority of its time in the public eye, the Bogotá Metro had one constant characteristic: it had been envisioned as an underground system.

The idea of opting for an elevated line instead – which has recently gained approval – was first put forward in 2015, following an engineering appraisal conducted by SENER on behalf of the national government.

Bringing the system above ground has drawn some strong controversy, particularly from Peñalosa’s political opponents, who voiced concerns regarding the noise and visual pollution an elevated metro system would cause, as well the potential knock-down effect on property prices.

The city municipality’s staunchly defends the idea of building it overground. Firstly, it maintains that an elevated line would be 28% cheaper to operate, while the construction time would be reduced from 66 to 40 months. The risks associated with digging underneath Bogotá were also found to be too high to justify, due to the need to excavate under bodies of water and the desiccation of the soil.

"Its construction will have fewer risks than an underground one,” Peñalosa said. “With a much more profitable investment we will reach 72nd Street, we will transport more people and will be connected with [Bogotá’s cableway system] TransMicable, with [bus rapid transit] TransMilenio, and with feeder trunks with a single integral rate. Savings from an above-ground system could allow a bigger and better metro in the future.”

The plan is still somewhat uncertain, mainly due to the city’s rocky political climate: throughout 2017, Peñalosa was embroiled in a battle to keep his mandate after a handful of citizens’ groups called for his recall. What’s more, as of November last year, the local press was reporting a ‘race against time’ for the official funding partnership to be confirmed, before something known as the Law of Guarantees would kick in.

The law, which came into effect on 11 November, prohibits public officials from tying their names to big public schemes within four months of an election. Presidential elections will be held in Colombia on 27 May 2018. For the time being, Bogotans are still awaiting the final word on whether the virtually mythical metro will actually become a reality.