WMG says a unique braiding method allows for numerous materials to be used

Frame development

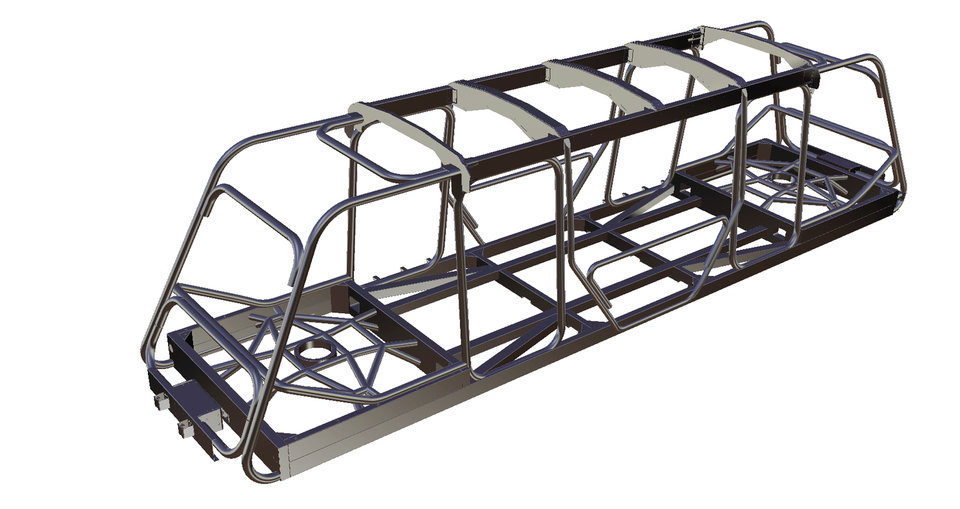

In May 2019 the group announced it had developed a vehicle frame, made from weaved or braided carbon fibre composites into a series of tubes. “We're looking particularly at carbon-based mouldings,” explains TDI’s managing director Martin Pemberton.

Image: NS3270 | shutterstock.com

Comprising thermoplastic tubes, the frame’s beams are customisable, with the same outer diameter but an inner wall thickness that can be adapted to suit the position the beam takes on the vehicle. Joining is standardised, cutting manufacturing costs though an automated process able to produce over a mile of tubing a day.

It also means should a part be damaged or compromised, it can be replaced without the need for any significant structural work, using simple welding and adhesives techniques.

WMG says the unique braiding method allows for numerous materials to be used, including carbon, glass and aramid. “They can be combined with a huge range of thermoplastics, from low-cost polypropylene to high-end polyether ether ketone (PEEK) to create a material that suits the given application,” it said.

Cutting weight, space and more

Pemberton says the group has been looking to cut the weight of the vehicle’s electric bogies too, often the heaviest part, as well other innovations. “We’re looking at advanced battery capability with rapid charging, sometimes in as little as two to three minutes; we're having to design this in such a way that we can build it into the floor to keep the centre of gravity load,” he continues. “A lot of it's about miniaturisation, being able to package things in the right way.”

Making components smaller yet easily accessible has been a challenge, Pemberton says, but doing so was essential. “We were asked to move a certain number of people in the vehicle and keep the vehicle length down to about 10m. The target was to keep the weight of the vehicle less than one tonne per linear metre of the train.”

Each electrical component has been designed for space, ease of access and to reduce the need for maintenance intervals. Many of the traditional parts have been replaced with plug-and-play units which can be swapped easily.

“The majority of systems are electrically operated, which immediately takes one skillset away from the maintenance requirement… If we've got no fluids in the vehicle, for example, you haven’t got to keep topping up levels. Take a bogie, if there's a problem we won't repair it on the vehicle, we’ll simply put a new one on. The same with the air conditioning and the control system.”

As well as cutting weight and maintenance, ultimately the vehicle will be driverless, offering a number of operational benefits, Pemberton says. “The whole concept only starts to become really commercially viable if you can take the driver out of the vehicle. If you’ve got a lot of vehicles, that’s a lot of drivers and drivers are usually the highest cost element of any transit system.”

He adds that an automated network will allow more services to run with increased accuracy, saving money and improving reliability. “As we've got a large number of smaller vehicles, the idea is that the headway can be increased so you can have vehicles literally coming around the corner every few minutes”.

The whole concept only starts to become really commercially viable if you can take the driver out of the vehicle