Comment

Labour’s railway renationalisation should be directed at ROSCOs

Alejandro Gonzalez explains why Labour's push for renationalisation should focus on rolling stock companies, which continue to profit from taxpayer subsidies and send profits abroad.

Greater Anglia Train At Ipswich Train Station, Suffolk. Credit: cktravels/Shutterstock

The King’s Speech at the State Opening of Parliament has signalled a significant shift in Britain’s railway sector, with Labour’s reform agenda aiming to renationalise passenger rail services. Labour plans to complete this transformation by 2029, leveraging break clauses in existing contracts to accelerate the process.

The forthcoming legislation will also establish Great British Railways (GBR) as a new public body to oversee the country’s railways. This transition aims to improve service quality, enhance productivity, and reduce costs by eliminating fees paid to private operators.

Privatisation & ROSCOs

The privatisation of the UK’s railway system in the 1990s under John Major’s government resulted in the establishment of train operating companies (TOCs) and rolling stock companies (ROSCOs). TOCs were created to operate specific routes under franchise agreements.

However, in September 2020, amid the Covid-19 pandemic and after 24 years, the government announced plans to terminate franchises for UK rail. Meanwhile, ROSCOs were established to own the passenger carriages and engines leased to TOCs and continue to operate in this capacity.

The pandemic lockdowns heavily impacted the profitability of TOCs, with revenues collapsing and government subsidies stepping in to keep the sector afloat.

According to Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee, passenger train companies received £4.4bn in subsidies in the 12 months up to March 2023, the latest year for which data is available. This amount marked a significant decrease from the £11.7bn provided by taxpayers to support the passenger rail industry during the financial year 2020-21. In contrast, in pre-pandemic 2019, passenger train companies required just £1.7bn in subsidies.

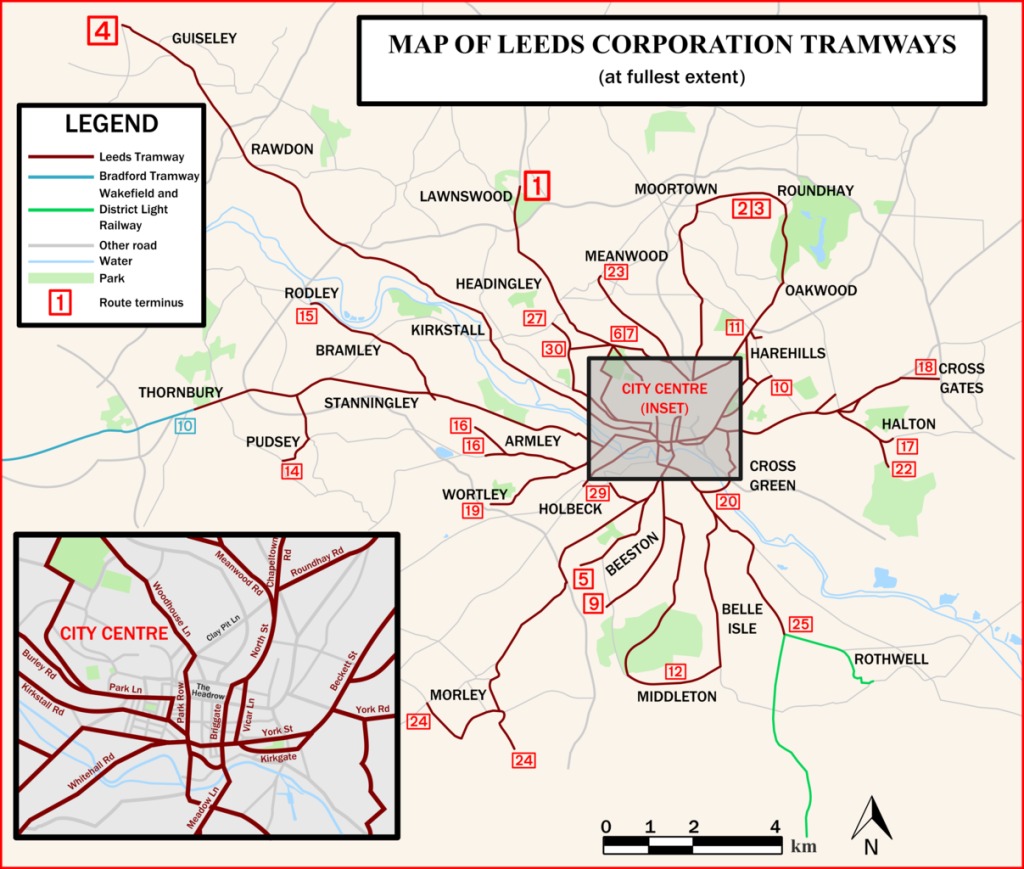

The Leeds tram network at its peak, including links to Bradford and Wakefield. Credit: Rcsprinter123 / Wikimedia, CC BY 3.0

In contrast, ROSCOs have thrived. According to the Office of Rail and Road (ORR), ROSCOs paid £409.7m in dividends in 2022-23, with profit margins soaring to 41.6%, as cited in The Guardian. These companies have benefited from “hell or high water” clauses in their contracts, ensuring lease payments continue despite falling passenger revenues.

Financial analysis by the ORR highlights that leasing costs for train operators fell slightly to £3.1bn last year, but still remain nearly 30% higher than five years ago, The Guardian reported in February this year.

The substantial profit margins and dividends of ROSCOs reflect a corporate arrangement where risks are socialised, and rewards are privatised. With taxpayer subsidies twice as high as pre-pandemic levels, the public effectively underwrites the £3.1bn spent annually on leasing trains.

Who are the ROSCOs?

The three main ROSCOs – Eversholt, Porterbrook, and Angel Trains – were created during privatisation and maintain their dominance today, despite government efforts to bring in competition.

Over the past decade, they have paid cumulative dividends of around £2bn. Eversholt, a subsidiary of CK Hutchison, paid £40.7m in dividends in 2022. Porterbrook, owned by a consortium led by Allianz and AIM, paid £80m. Angel Trains, majority-owned by PSP, paid £124.6m.

Rail union RMT’s research indicates that Angel, Eversholt, and Porterbrook paid out nearly £1bn in dividends during 2020-21, despite significant taxpayer support to the industry. Much of these dividends went to overseas entities based in Luxembourg and Jersey.

The elephant in the room

As Labour moves towards nationalising TOCs, the public purse continues to subsidise ROSCOs' profits and dividends, suggesting these firms are prime candidates for nationalisation. But the political appetite for such action is lacking. Keir Starmer's Labour prefers to address the widespread 'market failures' exhibited by TOCs in recent years.

However, under the existing arrangements railway leasing firms enjoy a highly advantageous position, and given the high entry costs for ROSCOs, a degree of competitive protection and unwarranted public subsidy.

Labour’s renationalisation efforts should focus on these ROSCOs. By targeting them, the government could reclaim a substantial portion of public funds currently diverted to private profits. This approach would ensure that the benefits of public ownership extend beyond operational services to include the assets and infrastructure critical to the railway system.

Renationalising ROSCOs would address the core inefficiencies and inequities in the current setup, providing a more sustainable and equitable future for Britain’s railways. It’s time to reconsider the distribution of risks and rewards in the railway sector, ensuring that public funds serve public interests.

The mine’s concentrator can produce around 240,000 tonnes of ore, including around 26,500 tonnes of rare earth oxides.

Gavin John Lockyer, CEO of Arafura Resources

Total annual production

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Production challenges for rare earth supply chains

There are two key issues with the production of REEs. First, all the rare earth deposits are mixed together, so it is difficult and expensive for processors to separate them and to take advantage of their individual properties. It is similarly challenging to split up the more valuable ones, such as terbium, from those of little value, like lanthanum.

Second, REEs are bound up in mineral deposits with the low-level radioactive element, thorium, exposure to which has been linked to an increased risk of developing lung and pancreatic cancer.

These obstacles create a huge challenge for any Western company that wants to become involved in the industry. However, they must be overcome if the Western world is to end its dependence on China.

Caption. Credit:

The biggest rare earth mines are located in China, and this source of domestic production has helped drive Chinese dominance. The Bayan Obo deposit in Inner Mongolia, north China – containing 40 million tonnes of rare earths reserves – houses the world’s largest deposits. The mine has been in production since 1957 and currently accounts for more than 70% of China’s light REE production.

However, Western mines are aiming to change this balance of production and power. The Mountain Pass Mine, owned by MP Materials , a Las Vegas-based mining company, is an open-pit mine of rare earths on the south flank of the Clark Mountain Range, 85km south-west of Las Vegas. In 2020, the mine supplied 15.8% of the world’s rare earth production and is the only rare earth mining and processing facility in the US.

In October 2020, Donald Trump, the former US president, signed an executive order declaring a national emergency in the mining industry, aimed at boosting the domestic production of rare earths. Trump ordered his cabinet to study the matter, with a view towards giving government grants for production equipment and imposing tariffs, quotas or other import restrictions against China.

The move, it said, would “allow the US Government to leverage the resources of its closest allies to enrich US manufacturing and industrial base capabilities and increase the nation’s advantage in an environment of great competition”.

The move, it said, would “allow the US Government to leverage the resources of its closest allies to enrich US manufacturing and industrial base capabilities and increase the nation’s advantage in an environment of great competition”.