Feature

The rise, fall, and rise again of the Leeds tram

The announcement of the West Yorkshire mass transit system is the latest chapter in a storied history of trams in Leeds. Peter Nilson explores the matter.

Render of the West Yorkshire mass transit system tram passing through Leeds City Centre. Credit: West Yorkshire Combined Authority

For many years, the UK city of Leeds has held the rather unfortunate distinction of being the largest city in Europe without a mass transit system. But that now looks set to change, with the new proposal of a West Yorkshire mass transit system.

The new project proposes to connect the cities of Leeds and Bradford, the two largest cities in the West Yorkshire Built-up Area – previously known as the West Yorkshire Urban Area.

The West Yorkshire Built-up Area, which also includes the city of Wakefield and the towns of Huddersfield and Halifax, is home to approximately two million people, making it one of the four major ‘built-up areas’ in the UK – alongside Greater London, Greater Manchester, and the West Midlands – according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The new West Yorkshire mass transit system project is the latest chapter in the long history of tram services in Leeds, and could potentially grow to become a wider mass transit system for the whole West Yorkshire Built-up Area.

Leeds used to have trams

Like many towns and cities in the UK, trams used to be a common sight in Leeds. The first horse-drawn tramways were introduced in Leeds as far back as 1871 and were some of the earliest forms of public transport in the city.

By 1891, the Leeds Corporation Tramways had been formed and took control of tram services in the city from the private companies that had operated them to date. This municipalisation of tram services led to the network growing and towards the end of the 19th century, the transition to electric trams began, with the first electric tram operating in Leeds in 1901.

By the 1920s and 1930s, the tram network in Leeds had hit its peak, enjoying its highest ridership numbers and covering much of the city, as well as connecting to the nearby cities of Bradford and Wakefield.

The Leeds tram network at its peak, including links to Bradford and Wakefield. Credit: Rcsprinter123 / Wikimedia, CC BY 3.0

But the rise of private motor vehicles and buses in the following decades saw a decline in tram usage, and the decision to prioritise buses as the prime mode of public transport for the city led to declining ridership and the closure of routes, with tracks being ripped up to repave roads for cars.

The story of tram services in Leeds follows the same pattern as many cities in the UK. The last tram service in Leeds ran on 7 November, leaving only two other cities in the UK operating trams – Sheffield ran its last service in 1960 and Glasgow in 1962. But by the 1990s, the idea of reintroducing trams in Leeds – as with many cities across the UK – was gaining momentum.

What was the Leeds Supertram?

The Leeds Supertram project was an ambitious plan to develop a modern light rail system in the city, which was ultimately cancelled in 2005.

Initially proposed in the 1980s, formal proposals for the Leeds Supertram began to take shape in 1991 when the initial planning and feasibility studies were conducted. The UK government announced its support for the project in 1995, with provisional approval from the Department for Transport (DfT) coming in 1997.

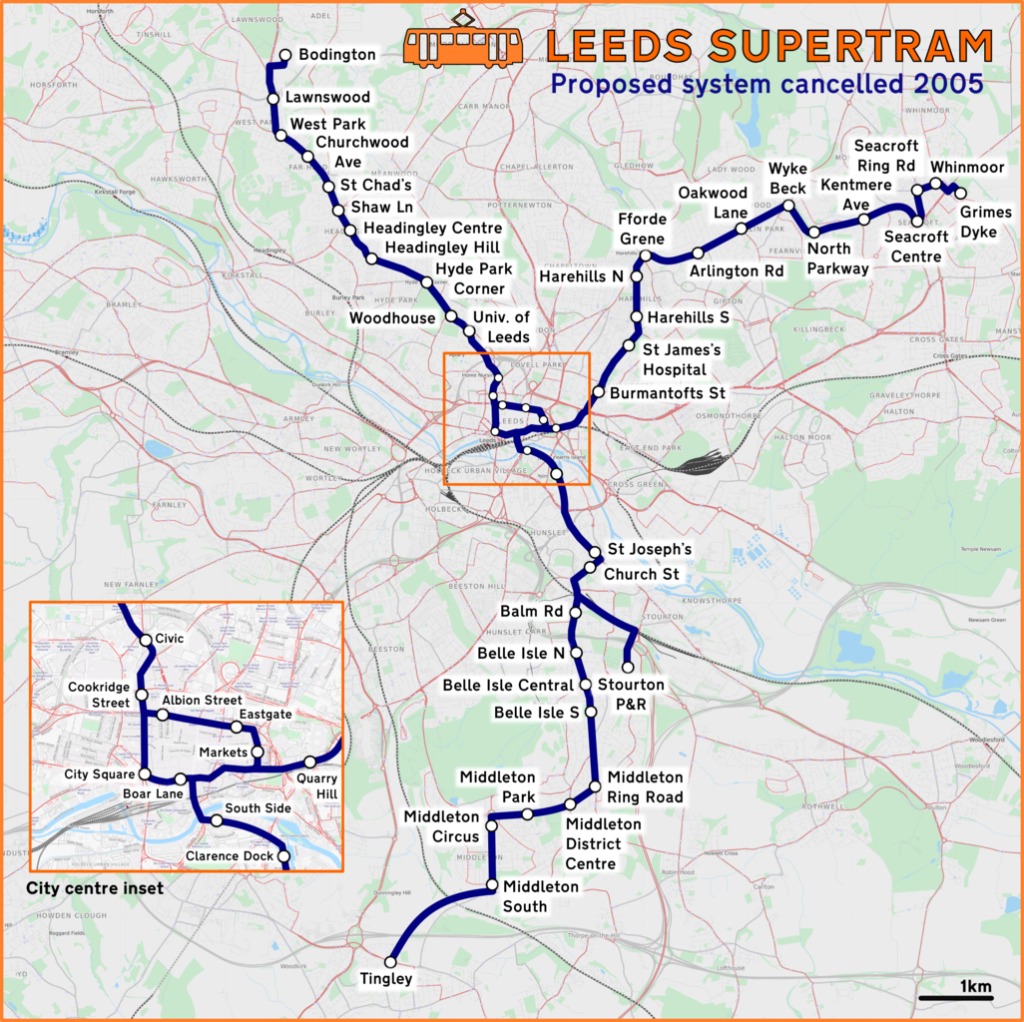

The proposed network would have consisted of 50 stations on three lines, with a total length of 27km (17 miles). The three lines would converge in a loop in the city centre, offering connections to bus services and train stations.

The Northern Line would serve several of the universities in the city, as well as the suburbs of Headingley and Lawnswood. The Eastern Line would have run from the city centre to the suburbs of Seacroft and Whinmoor while the Southern Line would run to the served Hunslet, Belle Isle, and Middleton suburbs.

There were hopes that following the construction of these routes in Leeds, further lines would be subsequently built, including a connection to nearby Bradford.

In 2001, the Supertram received parliamentary approval through the Transport and Works Act Order, allowing for land acquisition and construction, as well as a commitment to fund 75% of the construction costs using money from the central government.

The proposed Leeds Supertram routes. Credit: Wikimedia, CC BY 3.0

The first signs of trouble came in July 2004, when the Labour government, led by then-Prime Minister Tony Blair, withdrew financial support for the project, citing rising costs. The project was estimated to require £1bn investment, despite estimations just two years prior sitting at around half that figure.

Despite the project relaunching in November 2004 with a reduced cost – through reducing the length of the track by a total of 7km (4 miles), amongst other things – the Leeds Supertram project was running out of steam and there was diminishing political will from Westminster to continue its pursuit.

In 2005, The Leeds Supertram project was officially cancelled due to lack of funding. The decision by then-UK Transport Minister Alistair Darling came despite significant local support and the completion of considerable preparatory work that had already totalled a cost of £40m.

In the years that followed, there were various attempts to resurrect a mass rapid transit project in Leeds, including tram-trains, trolleybuses, very light rail, and more bus routes. However, following the cancellation of the eastern leg of HS2 in the Integrated Rail Plan published in 2021, the West Yorkshire region was promised funding for a mass transit system as a consolation.

What is the West Yorkshire mass transit system?

In 2022, Leeds City Council and the West Yorkshire Combined Authority (WYCA) began exploring new proposals for a £2.5bn modern mass transit system. In March 2024, West Yorkshire mayor Tracy Brabin announced plans for a tram system running between Leeds and Bradford – named the West Yorkshire mass transit system.

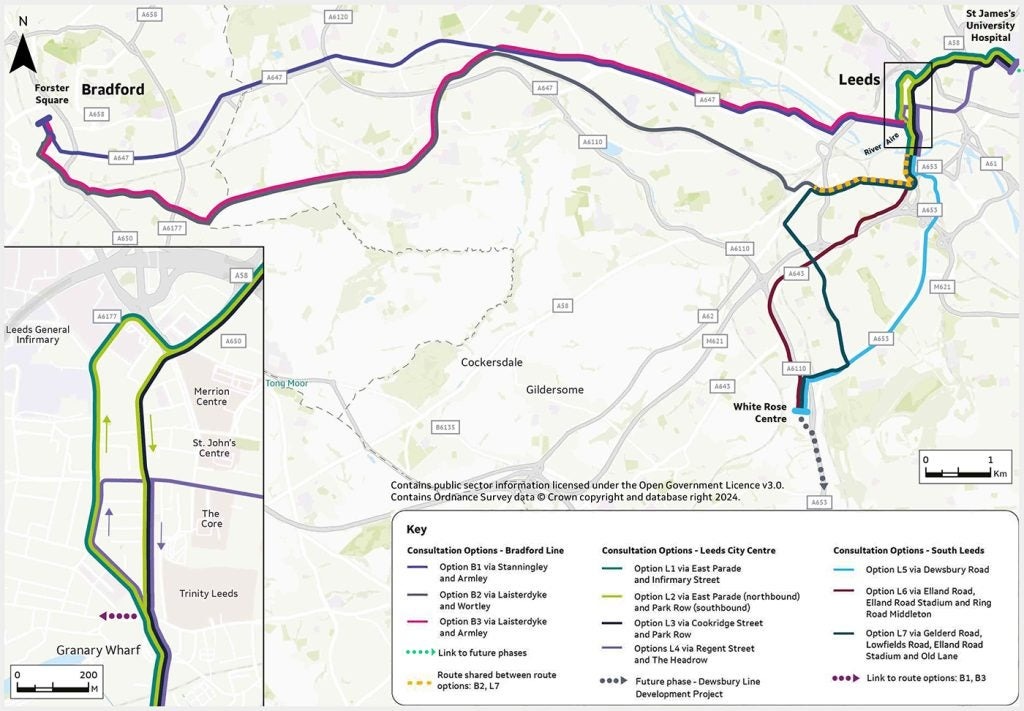

The project proposes two initial routes. First is a line across Leeds City Centre to South Leeds, and second is a connection between Leeds and Bradford. There are several options for each route, with a two-month public consultation currently underway to help decide the exact route of each line.

All potential phase one options for the Leeds Line run from St James’ Hospital and terminate close to the White Rose Shopping Centre, with two route options also running close to Elland Road, which is the location of Leeds Football Club’s stadium.

The proposed Phase One route options for the West Yorkshire mass transit system. Credit: West Yorkshire Combined Authority

The Leeds–Bradford Line will connect Bradford and Leeds city centres, with the proposed route options aiming to connect the Bradford suburbs of Thornbury and Laisterdyke, as well as the Leeds suburbs of Pudsey, Armley, and Wortley.

WYCA is planning a further consultation in 2025 once these routes have been identified, which will look further into the infrastructure required – including proposals on tram stops, depots, park and ride options and engineering works.

This new West Yorkshire mass transit system could be viewed as a watered-down version of the Supertram project that preceded it, but its advocates hope that it will act as a realistic and achievable first step in building a better-connected Leeds and West Yorkshire.

A diagram showing potential future routes in the West Yorkshire mass transit system. Credit: West Yorkshire Combined Authority

In conjunction with phase one of the project, consultations will take place with local authorities for the extension to the town of Dewsbury, south-west of Leeds. Efforts will also be made to explore future connections to Calderdale, south-west of Bradford; and Wakefield, south of Leeds.

Brabin has promised that spades will be in the ground as soon as 2028, and the core hubs created by the initial lines of the West Yorkshire mass transit system could well act as a foundation for further expansion, should the funding and political will be found in the future.

The mine’s concentrator can produce around 240,000 tonnes of ore, including around 26,500 tonnes of rare earth oxides.

Gavin John Lockyer, CEO of Arafura Resources

Total annual production

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Production challenges for rare earth supply chains

There are two key issues with the production of REEs. First, all the rare earth deposits are mixed together, so it is difficult and expensive for processors to separate them and to take advantage of their individual properties. It is similarly challenging to split up the more valuable ones, such as terbium, from those of little value, like lanthanum.

Second, REEs are bound up in mineral deposits with the low-level radioactive element, thorium, exposure to which has been linked to an increased risk of developing lung and pancreatic cancer.

These obstacles create a huge challenge for any Western company that wants to become involved in the industry. However, they must be overcome if the Western world is to end its dependence on China.

Caption. Credit:

The biggest rare earth mines are located in China, and this source of domestic production has helped drive Chinese dominance. The Bayan Obo deposit in Inner Mongolia, north China – containing 40 million tonnes of rare earths reserves – houses the world’s largest deposits. The mine has been in production since 1957 and currently accounts for more than 70% of China’s light REE production.

However, Western mines are aiming to change this balance of production and power. The Mountain Pass Mine, owned by MP Materials , a Las Vegas-based mining company, is an open-pit mine of rare earths on the south flank of the Clark Mountain Range, 85km south-west of Las Vegas. In 2020, the mine supplied 15.8% of the world’s rare earth production and is the only rare earth mining and processing facility in the US.

In October 2020, Donald Trump, the former US president, signed an executive order declaring a national emergency in the mining industry, aimed at boosting the domestic production of rare earths. Trump ordered his cabinet to study the matter, with a view towards giving government grants for production equipment and imposing tariffs, quotas or other import restrictions against China.

The move, it said, would “allow the US Government to leverage the resources of its closest allies to enrich US manufacturing and industrial base capabilities and increase the nation’s advantage in an environment of great competition”.

The move, it said, would “allow the US Government to leverage the resources of its closest allies to enrich US manufacturing and industrial base capabilities and increase the nation’s advantage in an environment of great competition”.