Analiysis

The Elizabeth Line is a success: so what about Crossrail 2?

Pyramid schemes: a look into Egypt’s megaprojects

Following the launch of the Elizabeth Line, Boris Johnson said that the UK Government should be “getting on with” building Crossrail 2. Andrew Tunnicliffe reports.

S

ince being officially opened by the late Queen Elizabeth II in May 2022, the Elizabeth Line continues to occupy column inches in the press; thankfully, largely for the right reasons.

In the final days of October the line’s Bond Street station – which will see as many as 140,000 passengers a day – opened to services and the public. A matter of weeks later and services linking Canary Wharf in East London – the capital’s financial district – and Heathrow Airport, 14 miles west of central London, finally became operational. The two had been delayed for months, at one point being as much as 18 months behind schedule, after a barrage of setbacks.

Construction of the almost £19bn project began in 2009 when then-London Mayor Boris Johnson helped lay the foundation stone at Canary Wharf. Marking its opening, Johnson, who by then was Prime Minister, unapologetically heralded the occasion and signalled he had even greater ambitions – of course not knowing then that he would be ousted from office in the weeks that followed.

“We have completed Crossrail [the Elizabeth Line],” he told ITV News, “but frankly, there is more that we should be doing.” He went on to detail work across London’s rail network that he felt would alleviate travellers’ woes, adding tax-increment financing would be a worthy consideration.

“I think the real thing for us now is to think about things like Crossrail 2,” he continued, “the old Hackney/Chelsea line, that is going to be transformative again.”

Brightline senior vice president, corporate affairs, Ben Porritt

What is Crossrail 2?

Crossrail – taking passengers from east to west, and back again – has provided a blueprint for other projects like it, namely Crossrail 2. The proposed scheme has a history similar to that of its forerunner – namely long and mired in proposals, objections and counter-proposals. It was first touted in the 1970s, travelling north to south linking Clapham Junction with Seven Sisters.

In the decades that have passed, plans have been drawn and redrawn, pushed ahead with and stalled; leading to the project being where it is today. Estimated to cost in the vicinity of £33bn – considerably more than the Elizabeth Line – current plans are a considerable enhancement of earlier variants.

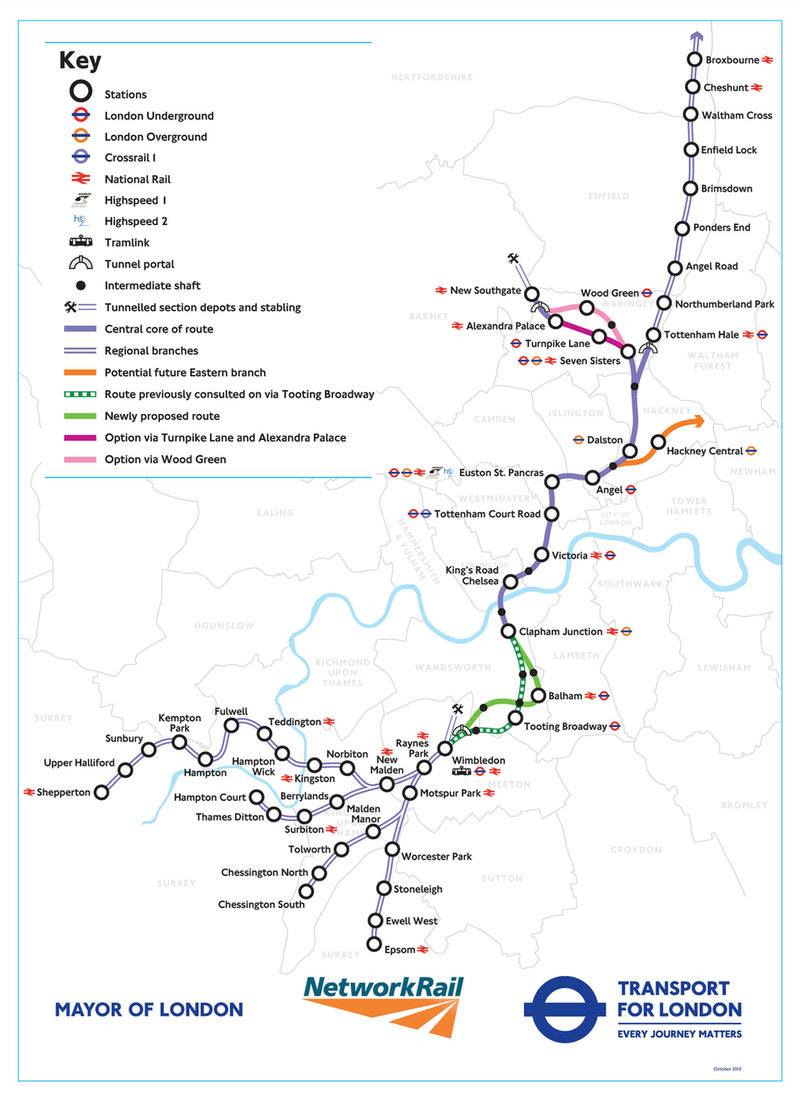

Today, its ambition stretches from Broxbourne, north of London in Hertfordshire, travelling south and branching off at Wimbledon with four final destinations in Surrey using existing rail lines, including Shepperton, Hampton Court, Chessington South, and Epsom. The 2015 consultation map shows almost 50 stations, offering access to other London Underground, Overground, and National Rail services via a network of interchanges.

The scheme is being jointly developed by Transport for London (TFL) and Network Rail, with support from the Department for Transport and sponsored by the Mayor of London and the Secretary of State for Transport.

The proposed route map for Crossrail 2, running from Southwest London’s suburbs to the Hertfordshire commuter belt. Credit: Crossrail 2

The project says that once completed, which is anticipated to be in the 2030s, it will increase London’s rail capacity by 10%, bring up to 30 trains per hour to destinations across the network, ensure 800 stations across the UK are within one interchange of London, provide additional capacity for up to 270,000 more people to travel into the capital during peak periods, and relieve congestion and overcrowding on Tube and regional rail services.

By 2030 it is expected that London’s population will have grown to 10 million, a million more than it is today. According to Crossrail 2, that will equate to an additional 5 million journeys across the capital’s transport network each year. “Crossrail 2 would give our transport network the extra capacity we need to keep the wider South East working and growing, and to make life here better,” it says.

The benefits the project might bring in terms of reduced journey times and improved access to London and its constituent parts would not be reserved for Londoners, according to the project. It says they would stretch across England from South East to South West, the Welsh borders across the Midlands to the East of England, as far north as Lincolnshire. Around 35% of today’s UK rail network (over 800 stations) would have a direct service to a station served by Crossrail 2.

“Connecting with so many of the UK’s most intensively used rail lines would help improve national connectivity,” Crossrail 2 says.

As well as the enhancements the project would bring to London’s transport network, it would have some important social and community benefits too. Among them are the development of 200,000 new homes and 60,000 new jobs across the UK supply chain (a further 200,000 once completed), according to the project’s leadership. But Crossrail 2 is a scheme “for the future of the whole country, not just London” it says.

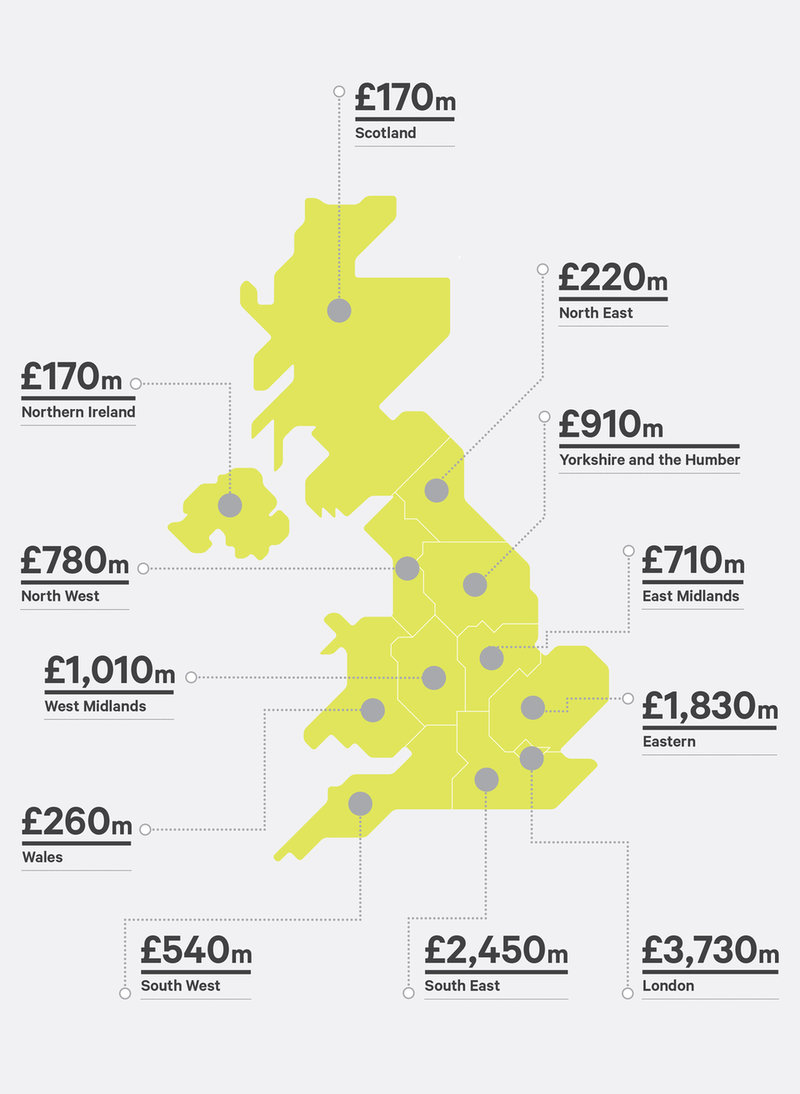

According to figures, the first Crossrail project saw 96% of its contracts going to UK-based companies, nearly two-thirds of which were based outside of London. This, it says, is something this project could do too, generating as much as £5bn worth of business for the UK’s small and medium-sized enterprises alone. Naturally, the lion’s share of the spread would be for England, but businesses in Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland are also expected to secure orders should the project go ahead.

Will it leave the station?

The question is, will it go ahead? Like so many major infrastructure projects, that is not easily answered. Crossrail 2 is not unique, it too suffers the on-off vagaries of any other large, multibillion-pound project in the UK and across many other developed countries. The issue, as is almost always the case, is funding and as such political will.

As the shadows grew long on Johnson’s tenure in office, he continued to acclaim the virtues of the project. However, funding has been an issue of much debate and concern for all parties.

The UK Government has been steadfast in its assertion that London should fund the majority, largely through TfL and private partnerships. In 2014 an independent review by PwC suggested that over half of the costs could be met by London using existing funding mechanisms.

Despite political support at both local and national levels, the project hit the buffers in the following years. In 2016 things seemed to be falling into place for the project to gain momentum, with the government allocating funds following a series of consultations. However, the project was again bogged down with funding concerns and affordability reviews.

Following the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, TfL faced a financial blackhole as passenger numbers – and thus its revenue – collapsed. It has since had to rely on short-term funding deals from government coffers; until recently when a more permanent funding package was agreed upon. As such, Crossrail 2 was seemingly shelved – at least for now.

Map showing the estimated regional Crossrail 2 supply-chain spending. Credit: Crossrail 2

Project leaders admitted in late 2020 that they were not in a position to confirm when work could restart as a result of TfL’s “current finances and the lack of a viable funding package for the scheme”.

They added: “Crossrail 2 will still be needed in future to support London’s growth and we have clearly demonstrated the case for the scheme. The project has been put in good order, ready to be restarted when the time is right.”

Along with the call from Johnson to revive the project in mid-2022, the new financial package with the UK Government led some to hope the project was back on track. The package still leaves TfL with an £800m annual deficit, meaning major projects remain in doubt. In his final days in office, TfL Commissioner Andy Byford warned it remained the case that TfL was facing financial challenges.

“The deal wasn’t as much, in terms of quantum, or as long in duration, as we would have wanted. So, we’re not suddenly able to say all of the projects are back on track,” Byford said. His departure from the role – and the loss of his enthusiasm for the project – will prove to be a further challenge for the project if it’s to regain momentum.

But Byford remained somewhat optimistic on the future of Crossrail 2: “I like to think that we won’t be in this situation forever, we will move to sunnier uplands. There will come a point where we are able to do more, but I should just manage people’s expectations: big ticket items are not on the horizon right now.”

Main image: The world-famous Flying Scotsman steam engine running on the East Lancashire Railway. Credit: Karl Weller/Shutterstock