All images: Max Bögl

Long read | High-speed

The UK doesn’t yet have the high-speed infrastructure to ban domestic flights

Banning UK short-haul domestic flights may be good for the environment, but such a move lacks government support. Despite similar moves on the continent, Peter Nilson argues that the UK railway isn’t a viable alternative yet.

A new report is calling for the UK Government to ban short-haul flights if the UK is to hit its carbon reduction targets.

Called ‘Trains over Planes: why the government should encourage domestic train travel’, the report was published by UK think tank The Intergenerational Foundation (IF).

It outlines the environmental argument for a short-haul flight ban in the UK and the shortcomings of the aviation sector in hitting its environmental targets.

Aviation is the most environmentally harmful mode of transport and is notoriously hard to decarbonise, with the industry having missed 49 of the 50 targets it has set itself over the past 20 years.

A ‘great modal shift’ from aviation to rail would lead to huge gains in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Studies have shown that the choice between air and rail travel most commonly comes down to travel time. Other factors include cost, as well as comfort and service frequency, while the reliability of service is also a decisive factor.

“Banning domestic flights with a viable alternative by train would be a faster route to our net-zero targets and a small but important contribution to protecting future generations from the effects of climate change,” says IF co-founder Angus Hanton.

However, looking at the UK’s current transport infrastructure, as well as the track record of recent UK governments, any move to ban UK short-haul domestic flights is nigh-on impossible.

SkedGo CEO John Nuutinen. Credit: Skedgo

MOTIONTAG managing director Fabien Sauthier. Credit: MOTIONTAG

Echoing domestic flight bans in Europe

In the report, the IF calls for a ban on all domestic UK flights where an alternative route via rail under 4.5 hours is available. It calculates a resulting 53% reduction in CO2 emissions from domestic flights within Great Britain and a 33% reduction in CO2 emissions from all of UK domestic aviation.

This will evoke a sense of déjà vu for those familiar with France’s recent decision to ban short-haul domestic flights where an alternative rail route under 2.5 hours is available. Yet the fact remains that this move is only possible thanks to France’s high-speed rail network.

“If the French can ban domestic flights with a rail equivalent, so too can the UK,” writes MP Wera Hobhouse in the foreword of the report.

TGV is France's intercity high-speed rail service, operated by SNCF, the national rail operator. Credit: Hadrian | Shutterstock

France has been investing in its high-speed rail network for the last 40 years. The country can only enact this type of aviation ban on short-haul domestic flights because it already has a high-speed rail network able to absorb the extra capacity.

Similarly, following the Austrian Government’s bailout of Austrian Airlines in 2020, the airline was instructed to end all domestic short-haul flights from its schedule where an alternative train journey under three hours is possible. It’s been estimated that 80% of short-haul domestic flights in Austria can be replaced by rail journeys.

Elsewhere, while not banning domestic flights, Germany has doubled taxes on all short-haul airline tickets, in an attempt to encourage passengers to opt for travelling by rail as opposed to flying.

These efforts of a modal shift from air to rail on the continent are all dependent on two factors. One is a reliable, affordable high-speed rail network. The other is political will.

High-speed rail in the UK isn’t competitive – yet

Even though there is a high-speed network in the UK, it doesn’t compare to the network in mainland Europe. This is a problem if rail is to win the choice of passengers. While non-high-speed rail can compete with flying for journeys up to 400km, a high-speed railway is the best way to encourage the switch.

A 2016 report by the European Commission shows that high-speed rail can “compete well” with air travel for journeys up to 500km and can also “compete moderately” for journeys in the the 500km-1000km range.

The most popular UK domestic flight route, the 534km journey between London and Edinburgh, is a prime opportunity for a modal shift from air to rail. In fact, journeys between London and Scotland account for 57% of all domestic air travellers.

So, high-speed rail has a chance to usurp flying as the de facto choice for many routes in the UK – if it exists as a de facto choice for long-distance routes.

A Eurostar train enters the Eurotunnel near Calais, France. The Eurostar uses the HS1 line in the UK. Credit: Antoine Antoniol/Bloomberg/Getty

At present, the UK arguably only has one ‘true’ high-speed line, HS1, which runs from London, through Kent, to the Channel Tunnel. Eurostar trains on HS1 operate at 186 mph (300 km/h), while the Southeastern Javelin service runs at 140 mph (225 km/h).

There are also high-speed services running on the East Coast Main Line, Great Western Main Line, Midland Main Line, parts of the Cross Country Route, and the West Coast Main Line; but these operate at a lower speed of 125 mph (200 km/h).

HS2 will extend high-speed rail in the UK, but the finished project will end up looking very different to what was initially proposed. The eastern leg to Leeds has already been scrapped, and there are fears of more changes to the project.

The UK has the potential for a high-speed rail network that can offer a real competitive alternative to flying.

HS2 has also already been considerably delayed, with the first phase between London and Birmingham now expected to open between 2029 and 2033. Phase 2 to Manchester and Marsden is now expected to be completed between 2035 and 2040.

The HS2 link to Scotland is no more, with plans scrapped In May 2015 when it was concluded that there was “no business case” to extend HS2 north into Scotland and that high-speed rail services should run north on upgraded conventional track. With that went a huge opportunity for true high-speed rail travel between London and Scotland.

That is all to say, the UK has the potential for a high-speed rail network that can offer a real competitive alternative to flying; but the chances of it happening are, for the time being, unlikely.

Cost and reliability play an important role

The IF report says that travel from city-centre to city-centre is only marginally slower by train than by plane in the UK – citing an average difference of 30 minutes travel time.

This broadly matches the situation with the French short-haul domestic flight ban, where French consumer group UFC-Que Choisir has estimated a 40-minute difference in travel time when comparing travel by train or plane between French cities.

Travelling between London and Manchester city centres, for example, is faster by train than by plane. But this journey is also a prime example of some of the reasons passengers might be unwilling to choose the railway.

Half a million flights were taken every year between London and Manchester before the pandemic. But post-pandemic, the London–Manchester rail service has been cut to a barebone timetable, with limited ticket availability.

Service on the West Coast Main Line is so dire that the UK Government has now placed franchise operator Avanti West Coast on a short-term contract and tasked it to deliver urgent improvements in services. Failure to do so could see services brought under operation by the DfT, similar to the way LNER and Southeastern are currently operated.

Even if people want to use rail, the fact that services can be infrequent, overcrowded, and often cancelled, can be off-putting.

Unreliable and infrequent service is a decisive factor in the choice to use rail, even if most of the time you can travel by train for a lower cost if booked in advance. The IF report shows a pricier average advance fare for UK flights compared to their alternative rail routes: £65.20 for flying compared to £59.70 for rail – not factoring in the additional costs of getting to or from an airport.

Further, the ongoing rail workers’ strikes in the UK do not help boost confidence in a reliable railway, even if the members of the public support the striking workers.

In August, the DfT published figures showing rail passenger numbers were at 95% of pre-pandemic levels, and projections show that ridership will soon exceed pre-pandemic numbers. People are getting back on trains, but timetables aren’t adapting to the increased demand.

This all contributes to an unfortunate situation. Even if people want to use rail, the fact that services can be infrequent, overcrowded, and often cancelled, can be off-putting. While this is frustrating for regular travel, for long-distance journeys this unpredictability is often a deal-breaker.

UK Government is funding aviation

Perhaps the biggest obstacle to any sort of short-haul domestic flight ban in the UK is the political will for one. Or rather, the lack of political will.

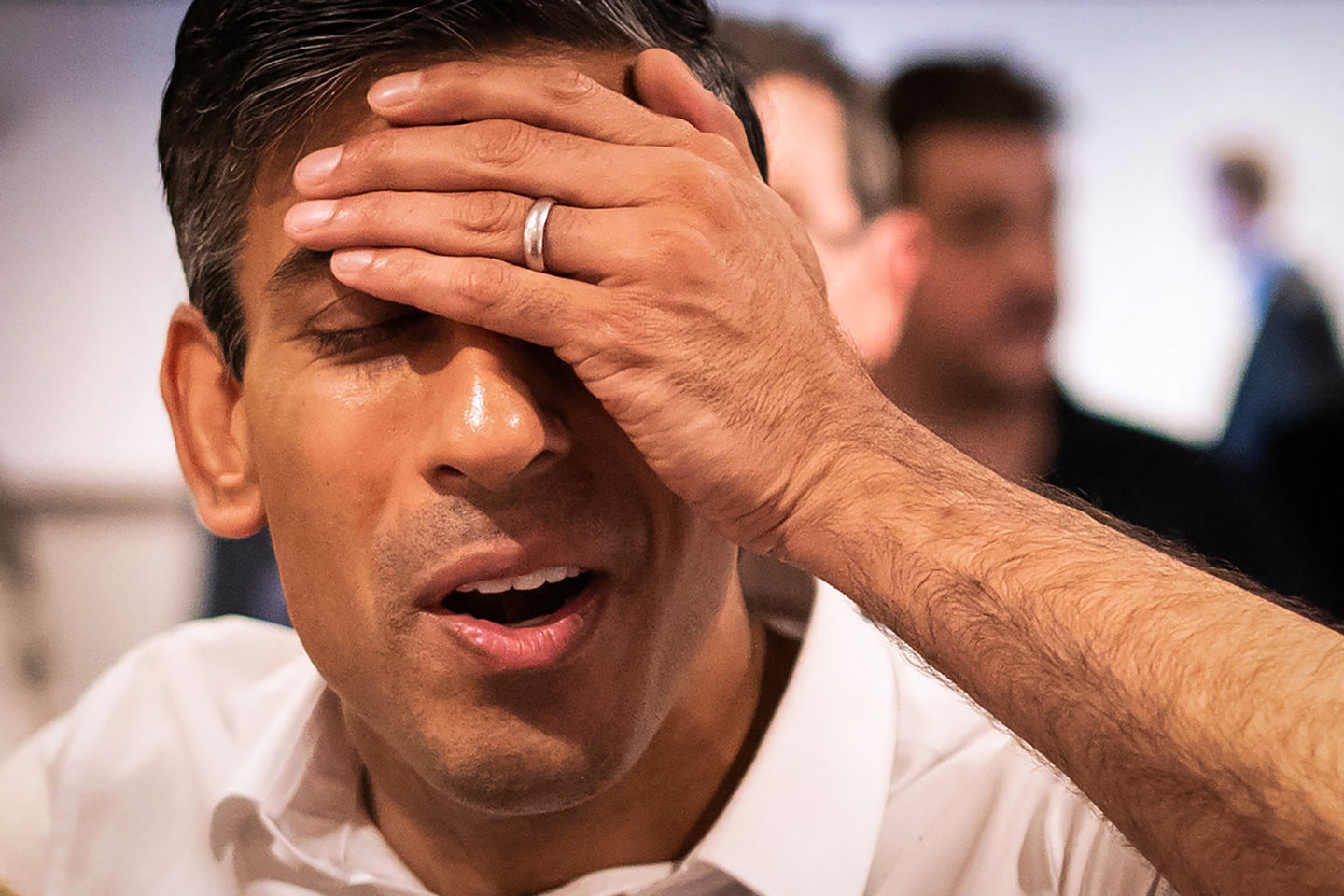

Where Germany increased tariffs on short-haul flights, the UK was accused last year of going “headlong in the wrong direction” by environmental campaigners, after then-Chancellor Rishi Sunak opted to reduce tax on domestic flights by half. Air Passenger Duty, which currently stands at £13 per ticket for domestic flights, will be reduced to £6.50 for domestic journeys in 2023.

The aviation sector was one of the most impacted by the pandemic, and the losses are still being felt today, despite recent recovery. Sunak’s Air Passenger Duty policy is indicative of the government’s willingness to help keep things afloat until passenger numbers return to pre-pandemic numbers.

But the IF report argues that VAT and fuel duty exemptions awarded to the aviation sector in the UK have now driven down the price of domestic flights – saying that “some estimates find that almost two-thirds of domestic flight tickets are cheaper than the rail alternative”. According to the IF, this makes travelling by plane “artificially competitive” against rail.

Britain's former chancellor to the exchequer Rishi Sunak announced cuts to air passenger duty weeks before the UK hosted COP26 in Glasgow. Credit: Joe Giddens/Pool/AFP/Getty

“As one of the fastest growing sources of greenhouse gas emissions, aviation has an important role to play in tackling climate change.

Those are the words of ex-UK Transport Secretary Anne-Marie Trevelyan, following the 41st ICAO assembly where members reaffirmed their commitment to reaching net-zero in international aviation by 2050.

Acknowledging the need to reduce aviation’s environmental impact, however, does not mean imposing any sort of bans according to the UK Government.

Instead, the DfT would prefer to encourage growth in sustainable aviation businesses, such as through its Jet Zero strategy; or improving efficiency in aviation operations, through its modernisation programme for UK airspace.

Rather than clipping the sector’s wings, our pathway recognises that decarbonisation offers huge economic benefits.

“Rather than clipping the sector’s wings, our pathway recognises that decarbonisation offers huge economic benefits, creating the jobs and industries of the future,” said Trevelyan's predecessor as Transport Secretary, Grant Schapps, during the Jet Zero announcement in July.

Through its actions, the UK Government has consistently recognised the economic importance of the aviation industry; according to the AOA, aviation contributes £51.97bn to the UK economy.

As such, it’s virtually impossible to imagine that any kind of UK domestic flight ban will be discussed by the current Conservative Government, let alone implemented, given the important contribution of aviation to the UK economy.

Given the newest Prime Minister’s apparent agenda being “an attack on nature“, if the choice is between reducing aviation’s greenhouse gas emissions or supporting the economic stimulus that aviation provides, it’s not hard to predict what the decision will be.